The biggest takeaway about the developing “law of coronavirus“ is that just as in society and politics, we are dealing with uncharted, novel territory in the legal arena — both substantive and procedural — and thus absolutely no one knows how things will eventually shake out. The law is a conservative, slow-moving insuitition that traditionally lags changes in society. And that is when the courts are open! I do not expect many or most of these issues to be settled any time soon. Imagine all the lawsuits arising from vendors, fans, partners, sponsors, insurance companies and the like affected by the suspension of all major sporting leagues and events this Spring. They will literally require years if not a decade or more to wind their way through the legal system.

So take the following as the best, informed guess from a lawyer who’s seen a lot in his 38 years of practicing the real world’s oldest profession. And one caution: things are in a state of very rapid change, so the information presented here may be outdated by the time you are reading this post.

- Law and Emergencies (Background)

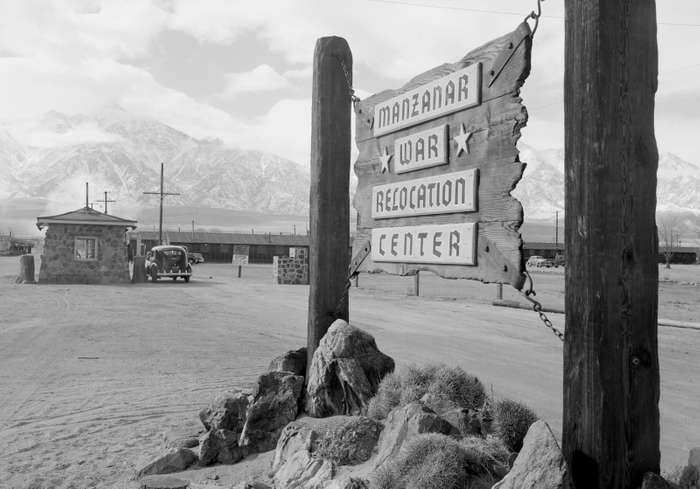

There’s an old adage in the law that “hard cases make bad law.” That is especially true in emergency situations, where courts are by their nature inclined to defer to the policy judgments of government’s political branches. Perhaps the best example is the Supreme Court’s now explicitly repudiated 1944 decision upholding the World War II internment of Japanese-American citizens against a constitutional challenge in Korematsu (“[T]he properly constituted military authorities…decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast.”)

This is an institutional tendency of the judiciary that will likely be seen in coronavirus decisions of much lower legal significance than the U.S. Constitution. That is, courts have a pronounced disinclination to upset settled expectations or to expand common law into new, sui generis areas where the state or federal legislatures have not acted. This suggests that, despite the somewhat harsh results reported below arising from application of existing precedent to emerging coronavirus legal issues, courts will remain hesitant to make new law and will be cautious in their use of the “unconscionability” doctrine to override contractual obligations of parties affected by the pandemic.

- Employment

When an employer decides (or is ordered) to close or reduce hours, can employees have their days or shifts reduced without compensation? This is just one of many employment issues already facing people affected by coronavirus shutdowns. Unfortunately, existing wage and hour laws like the Fair Labor Standards Act do not provide a reassuring answer.

Wage & Hours. The FLSA and parallel state laws require minimum wage, overtime pay rates, breaks, record keeping and the like, but do not compel employers to give hourly workers any specific minimum work availability. That is true even if an employee is on call, i.e., “waiting to be engaged,” which under existing law is not compensable. Shift reductions, so long as they do not reduce hourly pay rates to below minimum wage requirements, are lawful for “non-exempt” hourly workers. For exempt salaried employees, who have no overtime rights, that is by definition also the case.

Vacation & Sick Leave. A similar answer applies for whether employees can take paid time off (PTO) while furloughed or laid off. Most state laws provide that while accrued PTO does not have to be paid in cash on termination or resignation of employment, an employee is nonetheless entitled to take all accrued vacation or sick time that has been earned. While there may be a difference between firings and layoffs, that difference is likely immaterial under most of those state statutory regimes. If new legislation — the Emergency Paid Sick Leave Act — passed by the House of Representatives is enacted, as is expected, employers with fewer than 500 employees will have to provide 14 days of paid sick leave to full-time employees (and a prorated number of days to part-timers) as well as protect the jobs of employees who (i) comply with a requirement or recommendation to quarantine due to exposure to or symptoms of coronavirus, or (ii) self-isolate because the employee was diagnosed with coronavirus. And the COVID-19 crisis has resuscitated policy calls to enact federal law mandating sick time and PTO for all employees nationwide.

Termination. Nearly all non-contract (and increasingly contract as well) employees are classified as “at will” for employment purposes. This means that in the absence of unlawful employment discrimination, they can be fired at any time, without notice, for any reason, no reason or even a reprehensible reason. Hence, if a business cuts back due to lack of demand or a government directive to close, its employees under existing law can be terminated outright, with no liability. Likewise, nothing currently prevents an employer from firing a worker who contracts the virus, unfair as that result obviously is in today’s environment. (Union-negotiated collective bargaining agreements may dictate a different result, however.) No court has construed coronavirus to be a disability for purposes of the anti-discrimination provisions of the Americans With Disabilities Act.

Luckily for employees, Congress is already working on further legislation that would address some of these inequities, for instance providing additional FMLA leave and compensation to employees laid off as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. And some employers are stepping up to act in a socially responsible manner. Best Buy, for instance, reported via email that “if an employee is sick or needs to take care of their children home from school, we are paying them,” and even with cutbacks, “we are paying affected employees for their regularly scheduled hours.”

- Events & Retailers

What about all of those suspended or canceled sporting and other public events and shuttered restaurants and retailers?

Act of God. An event organizer, sports franchise or restaurant has written or de facto contracts with season ticket and single-event purchasers, patrons, sponsors, venues, landlords, advertisers and many more. Whether the contract terms provide an explicit right to suspend or cancel, however, they generally include what is commonly referred to as an “Act of God” clause exculpating liability for natural disasters and similar emergencies beyond control of the event host. Those provisions are an exception to the archaic rule of absolute liability for non-performance and are routinely sustained by courts as a defense to claimed breach of contract.

Negligence Liability. The organizer of an event or owner of a place of public accommodation has a duty in tort implied by law to exercise reasonable care for the safety and security of attendees. The implications for non-canceled events (and for retailers remaining open) are clear. These businesses are required to take available, practical steps to minimize risks associated with transmission of the coronavirus, or face potential legal liability to injured patrons. That is why recent days have seen scores of announcements from supermarkets and other major U.S. corporations of the immediate steps that have been taken to ensure a healthy, virus-free shopping environment for customers.

State & Municipal Government Directives. Recent days have also seen a wide array of restrictions directed by state and local governments banning mass gatherings, requiring bars, restaurants and cinemas to close, and more. These are almost sure to be sustained as a defense to potential lability for organizers and business owners. Contract law has always said that a contract may be altered by statute — subject to constitutional limits on “taking” of private property — and that statutory law excuses performance if the subject of the agreement or its terms are rendered unlawful by a legislature. While emergency decrees and “guidelines” that do not formally have the force of law may appear different, courts react from experience as well as precedent. Given the deference to government emergency actions discussed above, it is likely these sorts of restrictions will be applied as a contractual defense even if not promulgated as law or if only suggested as a guideline.

Refunds. Ah, the giant of all issues. Who keeps the money? The short answer is that it is a matter of contract and as in Vegas, the house always wins. Nothing requires an event organizer to provide a refund, although many offer rainout substitutions and will refund or re-book as a customer relations matter. While there are narrow state statutes for some circumstances and one federal regulation — the FTC’s “unavailability” rule for retail sales rain checks if stock runs low — there are few of those laws in the entertainment, commercial and travel sectors.

- Travel

Americans have been forced to cancel or adjust travel plans, and have been subject to health screenings and delays, in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. What are their legal rights?

Travel Bans. The Trump Administration has decreed travel restrictions on US-EU travel and citizens traveling from China and Iran — resulting in large airport and customs dislocations for returning citizens — and Canada has almost completely closed its borders. That’s inconvenient and potentially costly, but unfortunately not something for which current law provides relief. The federal government has wide latitude to screen arriving citizens and foreigners for admission to the country. Just as with warrantless TSA airport gate checks, you may have a right to refuse screening, yet the lawful price of exercising that right can be to lose the related privilege of boarding the airplane or emerging through customs inspection. And the government is only liable to the extent it has waived sovereign immunity under the Federal Tort Claims Act, so the chances of obtaining compensation for any of this are quixotic even though Presidential proclamations do not necessarily have complete force of law.

Refunds. What about refunds if you must cancel travel or an airline or hotel is closed or operating at reduced capacity and cancels your reservations? The short answer is that there are generally no legal rights apart from any written contracts, which ordinarily do not require a refund. Refunds are a matter of business judgment and customer relations for most businesses — absent misleading statements, material nondisclosures or fraud. Most A+ rated travel companies allow refunds for coronavirus-caused cancellations as a matter of customer service, however. Delta, for instance, says that:

Whenever your travel may be, rest assured that all changes will be processed and applicable credits will be issued; if you don’t take your flight, your ticket number automatically becomes an unused eCredit within 24 hours. We promise to work through these issues and sincerely appreciate your patience.

Better businesses also react. Look to NBCUniversal, which is now offering all movies on demand immediately on release because many if most cinemas will be closed for the duration. In the longer term, that remarkable change to movie studio release “windows” may have much broader commercial implications for the future of move theaters and streaming video services.

Travel Insurance. Some consumers purchase travel insurance in connection with airline, cruise and hotel bookings. The reality for claims under such policies is that they are governed by the “fine print” of the policy terms. Most commercial travel policies insure against illness or injury to the traveler, not cancellations by the travel or hospitality provider. So while a large subset of states have rules against bad faith by insurance companies, a claim denial on the basis of policy exclusions is likely to pass judicial scrutiny even if litigation were a financially realistic option for the policy holder.

Re-entry and Quarantine. Readers can probably anticipate the answer here. Given the federal government’s wide authority over border control and re-admission, it is very unlikely — especially in the context of exigent circumstances — that a CBP or other government agency request or directive that an American citizen showing COVID-19 symptoms self-quarantine, self-isolate or be admitted to a hospital for a period of time would be reversed by the courts.

- Social Distancing

Lastly, let us turn to the new and daily-evolving guidelines on social distancing, “shelter in place,” public and private gatherings, and the like. Are there rights for consumers against businesses imposing restrictions people may find objectionable? What is the exposure if you disobey a guideline or state/local emergency public health directive?

Due Process. It is 100% settled, but often a source of lay confusion, that the constitutional right to due process exists only against the government, not private parties. This means that the ability to challenge private restrictions for lack of notice or an ability to contest them is non-existent. So if a retailer, for instance, insists that people who in its subjective judgment exhibit symptoms of COVID-19 will not be allowed entry into the establishment, there is no legal recourse unless some independent grounds, such as racial or disability discrimination, exist. And perhaps obviously, as noted above no court has to date construed coronavirus to be a disability for purposes of Title VII or the ADA.

Individual Liability. Where a person decides not to obey government public health measures, the issues become a little murkier. Say you go out walking in San Francisco despite the mayor’s new shelter in place decree; can you be arrested? First, that’s unlikely as a practical matter because — so far at least — police are only issuing tickets for infractions, not making criminal arrests. Second, here there are traditional rights against the government, including to challenge notice and procedures leading to adoption under the Due Process Clause and to quash a warrantless arrest for absence of probable cause under the Fourth Amendment. In contrast, if you violate the rules applied by a retail establishment, whether reasonable or posted or not, there is no recognized legal basis to challenge being asked to leave or escorted from the premises.

Violating Personal Space in Public. Recent guidelines recommend keeping six feet of separation from others in public spaces. But might there be personal legal liability if one does not comply? The traditional rule is that violation of a statute is considered negligence per se, with tort liability possible as a result. But because most of the CDC and other guidance issued to date do not have the force of law, chances of a successful claim by another individual whose personal space is “invaded” are remote under current precedent.

Hoarding. Hoarding may land one on television or, in extreme cases involving a mental health disorder, in a family protective services proceeding. Hoarding, however, is not itself illegal. That is not to say that hoarding can have no consequences. Wegmans and other supermarket chains have reacted to widespread hoarding of toilet paper by limiting per-customer purchases. Once again, that is entirely lawful for a private business and consumers can be forced to comply or else denied the ability to purchase the voluntarily rationed products.

Disclaimer: Please note this blawg post is for general information and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice, nor does it establish an attorney-client relationship. If readers have questions about their specific circumstances, they should consult an attorney.

I think this is brilliantly written and most informative. Yes, it will be a most interesting few/many years of legal issues when the virus has rung itself dry. When will that be? If I had a crystal ball I might be able to answer my own question.

I DO remember, very well, in 1944, when the Japanese were interned, even if they were USA citizens at the time. A shameful issue in our past!

I have read several books, over the years, written by people who were involved as children, or teens, and often think about myself at that age, and how I would have felt had I been one of them.

Thanks mom! 😉

It is a good thing to leave footprints behind that leave a sense of what was going on during the time. This is one of those footprints, Glenn that is worth keeping around. Bring on more of them.

Judith