1. Antitrust and the Cable Bottleneck.

The first speech was from the head of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, Bill Baer. His address to an October 2015 Duke Law School conference on the Future of Video Competition and Regulation, titled “Video Competition: Opportunities and Challenges,” laid out the federal government’s policy framework for assessing broadband mergers and the state of competition in broadband Internet access services.

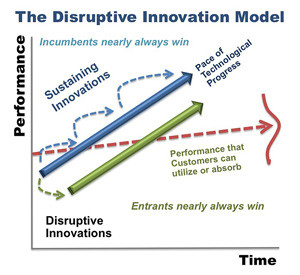

Starting from the premise that it is the role of competition policy and antitrust enforcement to “ensure that consumers continue to benefit from the extraordinary innovation we are witnessing,” Baer posited that developments like streaming Internet television and video on demand represent what

Antitrust enthusiasts like to call…disruptive innovation. Some innovation comes from incumbents smart and nimble enough to take advantage of these new opportunities. But new entrants deserve a lot of credit, too. Companies like Netflix and Amazon offer consumers flexibility and control; established players like CBS and HBO have been forced to respond.

Baer went on to assert that “today most consumers do not enjoy competition for high-speed Internet access.” That’s the rub. Not that he was wrong in pointing out that the economics of wired networks (with substantial capital expenditure requirements and huge sunk costs) both deter new entry and often give incumbents a significant pricing advantage. That’s “axiomatic,” to use Baer’s term. Rather, he was talking about what regulators have historically termed the “bottleneck monopoly” of cable television companies.

He may have been right on that point, too — although Google Fiber, Verizon FiOS, AT&T U-verse and municipal broadband networks like Chattanooga’s (boasting 1GB throughput) that provide what the city calls “Internet speeds that are unsurpassed in the Western Hemisphere” for “the entire community, urban or rural, business or residence” are both widely deployed and seem largely to have been overlooked in Baer’s analysis. The real problem is that Baer embraced and reaffirmed the Federal Communications Commission’s policy goals in video regulation as part of his bottleneck analysis, saying explicitly that the Antitrust Division “share[s] both space and point of view with the FCC.”

This is a sea-change in the antitrust position on regulatory efficacy. More than 30 years ago, when this author cut his eye teeth as a young law school graduate with the Antitrust Division, it was equally axiomatic that regulatory agencies could never control bottleneck monopolists and that antitrust enforcement needed to take regulatory policy as a given, “simply as another fact of market life” to work into its analysis. (In the United States v. AT&T monopolization case, for instance, two former FCC Common Carrier Bureau chiefs testified that the FCC “is not and never has been capable of effective enforcement of the laws governing AT&T’s behavior.”) Baer’s embrace of the FCC’s re-definition of high-speed Internet access to 25 MBps and its controversial Open Internet Order (more commonly known as network neutrality) discard that worldview in favor of one which implies regulation can indeed control anticompetitive behavior by bottleneck monopolists. I must respectfully disagree. While its motivations are usually laudatory, the FCC’s history is unfortunately more one of what scholars deem “regulatory capture” than effective use of regulation to preserve and enhance competition See my last Project DisCo article on set-top box competition for a sad, decades-long example.

While it is all well and good that the FCC and the Justice Department share information and cooperate in merger investigations, their roles are different; complementary, yes, but hardly parallel. That’s why, in 1982, DOJ’s Antitrust Division convinced the late district judge Harold Greene to break up the Bell System on the ground that the regulation was inherently ineffective and inferior to what the Supreme Court as far back as the famous 1961 Du Pont case called the “surer, cleaner remedy of divestiture.”

AT&T’s pattern during the last thirty years has been to shift from one anticompetitive activity to another, as various alternatives were foreclosed through the action of regulators or the courts or as a result of technological development. In view of this background, it is unlikely that, realistically, an injunction could be drafted that would be both sufficiently detailed to bar specific anticompetitive conduct yet sufficiently broad to prevent the various conceivable kinds of behavior that AT&T might employ in the future.

United States v. Western Elec. Co., 552 F. Supp. 131 (D.D.C. 1983). It would have been good, and more straightforward, if Baer had acknowledged this history and explained what has changed to justify the current Antitrust Division’s quite different perspective.

2. Competition and Disruptive Business Models.

The second speech was by the Federal Trade Commission’s Stephen Weissman, who until just a few days ago served as Deputy Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition. His November 4 address to the Annual Antitrust & Consumer Protection Seminar of the Washington State Bar Association, titled “Pardon the Interruption: Competition and Disruptive Business Models,” focused specifically on the policy issue for which the aforementioned Project DisCo blog is named — disruptive innovation.

The thesis of Weissman’s speech was how “disruptive business models play a role in our investigations and enforcement decisions,” more specifically how new innovation and prospects for future disruption affect antitrust enforcement in merger and unilateral conduct (i.e., monopolization) cases. Stressing that in modern, non-commodity markets, price effects are just a small part of the applicable antitrust merger analysis, Weissman used the 2010 Google-AdMob acquisition as his poster child. As Weissman explained (yes, it’s a long quote, but bear with me):

[T]he market for the development of advertising on mobile devices was just emerging, with changes occurring on many fronts, and our initial concerns ultimately were overshadowed by two subsequent developments in the market: (1) Apple’s acquisition of the third largest mobile ad network, Quattro Wireless, and (2) Apple’s introduction of its own mobile advertising network, iAd, as part of its iPhone applications package. Because of these changing circumstances, the Commission concluded that Apple quickly would become a strong mobile advertising network. The timing and impact of Apple’s entry in the market led the Commission to conclude that AdMob’s success to date on the iPhone platform was unlikely to be an accurate predictor of AdMob’s competitive significance going forward, whether AdMob was owned by Google or not. Accordingly, the Commission unanimously voted to close its investigation without taking action against the merger.

That is a sophisticated and, in my judgment, properly long-term view of disruptive innovation Today’s economy is not the relatively static, industrial-based, incrementally evolving one of 50 years ago. So attention to the dynamic interaction of new entry and “platform” competition makes perfect sense for antitrust enforcement. On the other hand, Weissman cautioned that “[n]ot every claim of disruptive competition survives close examination.” For instance, he observed, the FTC “recently succeeded” in blocking the merger of the two largest foodservice distributors in the country, Sysco Corporation and US Foods, because “the effect of ‘cash and carry’ alternatives was limited and this business model would not discipline broadline foodservice distributors, certainly not at any time in the near future.”

One can question whether Weissman’s conclusions represent overall FTC enforcement policy in light of the agency’s continuing hold on on a proposed Staples-Office Depot merger. After all, it seems apparent — given rapidly declining share and continuing losses — that dedicated office supply firms are losing out to big box retailers and business process outsourcing. Yet his balanced approach to the impact of disruptive innovation is enlightening because it indicates that at least some antitrust enforcement officials get it: the role of government should be to preserve and extend competition, not fashion market structure to their preferred end result

3. The FCC’s Competition Regulation Role.

By far the most provocative speech was that by the Federal Communications Commission’s current General Counsel, Jonathan Sallet. His add ress in September to the Telecommunications Policy Research Conference, titled “The FCC and Lessons of Recent Mergers & Acquisitions Reviews,” drilled down into the analysis, “some of [which] is in the public record, some is not,” used in three high-profile FCC merger reviews — Sprint/T-Mobile, Comcast/Time Warner Cable, and AT&T/DirecTV. As he correctly summarized, “[t]he first was not pursued, the second was abandoned and the third was approved, with important, pro-competition conditions.”

Sallet’s theme was that the FCC’s “public interest” standard adds value to the merger review process in communications markets independent of antitrust review and enforcement. Those are fighting words to some politicians and conservative policy wonks, who argue that the FCC’s merger activities represent regulatory overreach at its zenith. Sallet was unapologetic, insisting forcefully that

It has been said, wrongly in each instance that, because of our public interest standard, the Commission departs from close economic and factual analysis of transactions. As a result, it is alleged, that the Commission does not rigorously examine potential public benefits, especially when proffered by parties as voluntary commitments, that it does not add independent value beyond that supplied by the antitrust agencies, and that it does not ensure compliance with those conditions that are imposed.

So what, you may ask? These institutional and jurisdictional rivalries have been going on for a long time — witness, for instance, the polarized debate last year on whether the Federal Trade Commission should resist the FCC’s Open Internet Order reclassification of broadband as a “telecommunications” service on the ground that, under statute, that would strip the FTC of its consumer protection authority, which does not extend to regulated utilities.

The importance is that the FCC continues to insist its institutional competence is entitled to deference in the context of competition regulation. As Sallet put it, “[t]he broader legal standard entrusted to the Commission — namely the requirement that applicants demonstrate that their proposed transactions will further the public interest — is an appropriate means to look beyond the traditional strictures of the antitrust laws (most notably the Clayton Act).” It is in the context of the approved AT&T/DirecTV merger that this proposition is most debatable. According to Sallet, “the core concern came down to whether the merged firm would have an increased incentive and ability to safeguard its integrated Pay TV business model and video revenues by limiting the ability of OVDs [online video distributors] to compete effectively, especially through the use of new business models.”

What is problematic about this formulation is simple. As a competition matter, the FCC was right to examine the horizontal overlap between AT&T (via U-Verse) and DirecTV as providers of video television programming. Yet the agency’s “core concern,” as the eventual consent order conditions revealed, was the vertical relationship between programming distribution and content competitors. Here the FCC has a very poor track record, going all the way back to the much-heralded (and totally inefficacious) AOL/Time Warner merger of 2001. There, the FCC was concerned about instant messaging, and conditioned the transaction on a “voluntary commitment” by the parties to enhance instant messaging interoperability. The fact that most readers do not remember AOL Instant Messaging (AIM) or that, within just a few years, SMS messaging — i.e, texting — had totally displaced AIM, epitomizes the vagaries of such regulatory “conditions.” Regulators cannot predict the future evolution of markets any better than antitrust enforcers, arbitrageurs or venture capitalists.

It is hubristic to think otherwise, but this history reveals the truth of the old adage that “where one stands depends upon where on sits.” Sallet is a smart and creative lawyer. Yet his defense of the FCC’s institutional authority reveals more of the political economy of regulation than a merits-based justification for the FCC’s application of its merger review authority. Whether the competition regulation system in the U.S. will persevere under this scheme of dual, “complementary” agencies is hard to tell. It certainly will remain controversial, for sure.